When Harry Married Bob

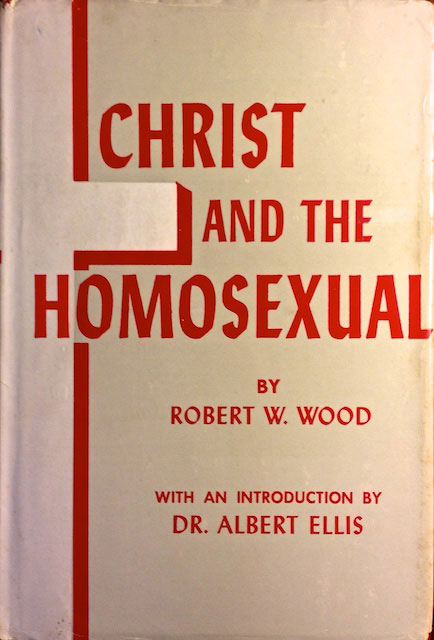

21/1/14 16:10In 1973 Harry Freeman married Bob Jones at Boston’s Old West Methodist Church. Having a Christian ceremony was important to them. They had both been students in seminary school, and although they chose not to pursue careers with the Church, they remained deeply committed to God, the Christian faith, and to the development of spiritual life on earth.

The night before their wedding the Bishop of the New England Conference warned them that if they proceeded with their ceremony they put Reverend William Alberts' career at risk. Alberts was the minister at Old West and, as we saw in the last post, he was deeply committed to a wide range of progressive social issues. He also was not easily intimidated. Just as he believed in openly fighting racism within the Church, he believed in the right of same-sex couples to marry. The wedding proceeded as planned.

Reproduced with the permission of the photographer

Well, not exactly. Many friends and even some family were invited to attend, but no one expected to walk into a church full to overflowing. Everyday Bostonians turned out to show their support for them as a couple and for the rights and dignity of lesbians and gays in general. Harry knows this because at one point in the ceremony they held an “open mic” session during which folks were invited to come up and talk about why they were there and what the day meant to them.

Of all the people to speak, there were two groups that Harry remembers most. The first were members of the local chapter of the National Organization of Women, the first and most influential national body to emerge from the 1960s women’s movement. These women’s presence is particularly significant because at that time NOW’s leadership was working hard to keep lesbians from having any kind of visible presence in the organization. NOW president Betty Friedan had in 1969 described lesbians in the organization as a “lavender menace.”

[click through to visit NYPL.org]

Issues of special concern to lesbians were not permitted on NOW’s official agenda until 1971. The women who went to support Harry and Bob stood up to say that their wedding was precisely the kind of thing NOW should be supporting.

The other memorable group to stand and speak was a typical-looking young, white, heterosexual couple with young children in tow. Unknown to Harry or Bob, they came simply to show their support for the newlyweds, and to stand in solidarity with the fight against prejudice toward lesbians and gays.

Not a single word of protest was breathed that day, despite the major media coverage leading up to the event. The “religious right” had not yet mobilized. That would come later.

I learned these details from Harry Freeman-Jones in a recent phone interview. I rely heavily on oral history to uncover the undocumented past, but luckily for us the entire ceremony was recorded by Boston’s local NPR radio affiliate. Hopefully I’ll soon be able to hear the voices of everyone who spoke that day. Hopefully. Who knows if the tape has been preserved?

The night before their wedding the Bishop of the New England Conference warned them that if they proceeded with their ceremony they put Reverend William Alberts' career at risk. Alberts was the minister at Old West and, as we saw in the last post, he was deeply committed to a wide range of progressive social issues. He also was not easily intimidated. Just as he believed in openly fighting racism within the Church, he believed in the right of same-sex couples to marry. The wedding proceeded as planned.

Reproduced with the permission of the photographer

Well, not exactly. Many friends and even some family were invited to attend, but no one expected to walk into a church full to overflowing. Everyday Bostonians turned out to show their support for them as a couple and for the rights and dignity of lesbians and gays in general. Harry knows this because at one point in the ceremony they held an “open mic” session during which folks were invited to come up and talk about why they were there and what the day meant to them.

Of all the people to speak, there were two groups that Harry remembers most. The first were members of the local chapter of the National Organization of Women, the first and most influential national body to emerge from the 1960s women’s movement. These women’s presence is particularly significant because at that time NOW’s leadership was working hard to keep lesbians from having any kind of visible presence in the organization. NOW president Betty Friedan had in 1969 described lesbians in the organization as a “lavender menace.”

[click through to visit NYPL.org]

Issues of special concern to lesbians were not permitted on NOW’s official agenda until 1971. The women who went to support Harry and Bob stood up to say that their wedding was precisely the kind of thing NOW should be supporting.

The other memorable group to stand and speak was a typical-looking young, white, heterosexual couple with young children in tow. Unknown to Harry or Bob, they came simply to show their support for the newlyweds, and to stand in solidarity with the fight against prejudice toward lesbians and gays.

Not a single word of protest was breathed that day, despite the major media coverage leading up to the event. The “religious right” had not yet mobilized. That would come later.

I learned these details from Harry Freeman-Jones in a recent phone interview. I rely heavily on oral history to uncover the undocumented past, but luckily for us the entire ceremony was recorded by Boston’s local NPR radio affiliate. Hopefully I’ll soon be able to hear the voices of everyone who spoke that day. Hopefully. Who knows if the tape has been preserved?