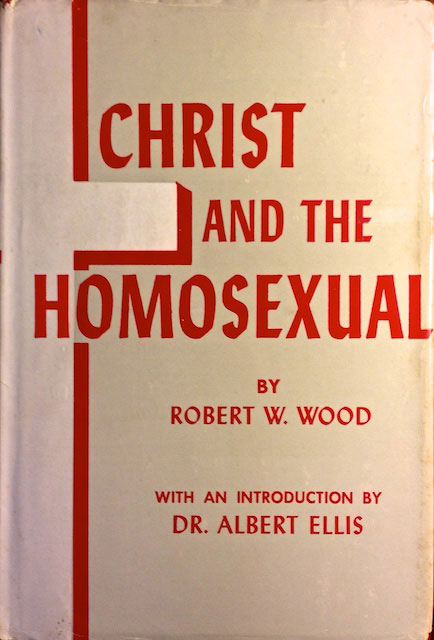

In the history of lesbian and gay politics, historians put a lot of stock in whether or not the people we study were "out." But what exactly does"out" mean? This past week I interviewed Robert W. Wood, author of 1960 bookChrist and the Homosexual. Wood is a retired United Church of Christ (formerly Congregationalist Church) minister who knew since high school that he was gay. As a teenager he poured through Biblical scripture looking for guidance regarding his sexuality and found none.

Two years after the book came out, Wood met, fell in love with, and married rodeo cowboy and artist Hugh Coulter. They bought and wore matching gold bands on their left ring finger but maintained separate residences. When congregants invited Wood out socially, Hugh usually went along. Some grasped the nature of their relationship, others did not.

Was Wood "out" or not? In an interview I conducted with him last week he says he "came out" in 1957 when he published a short article called "Spiritual Exercises" in a gay men's physique magazine. He used his real name and it was printed with a clear head shot, the same one he later used for his book. In an earlier interview with Stephen Law, Wood described an unambiguous public declaration of his sexuality more typical of what Americans consider "coming out." When Hugh died in 1986 a sympathetic parishioner said, "I am so sorry your friend has died."

"He wasn't my friend,"Wood declared, "he was my partner." It was the first time he confronted the ambiguity that had allowed him and Hugh to lead the life they did while still actively and openly advocating for gay rights.

Being "out" enabled people to publicly fight against oppression while simultaneously providing a visible role model for lesbians and gays who believed they were abnormal, deviant, and sinners. For that reason, being out had a measurable historical impact. Wood's book is case in point. He received hundreds of letters from lesbians and gays who expressed relief at having a positive view of themselves put forward, but who were still too afraid to sign their own names at the bottom of the page.

Did Wood come out in 1957 or 1986? Or is "outness" too blunt an instrument for understanding the history of queer resistance politics? Perhaps Wood's story suggests that we need a different metric for measuring "outness" in the 50s and 60s than we do for the 70s and after. What do you think?

(Special thanks to Alan Miller of the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives for putting me on to Wood's work)

crossposted to![[community profile]](https://www.dreamwidth.org/img/silk/identity/community.png) fromoutlawstoinlaws

fromoutlawstoinlaws

Like the Elise Chenier Facebook Page | Like the From Outlaws to In-Laws Facebook Page

Two years after the book came out, Wood met, fell in love with, and married rodeo cowboy and artist Hugh Coulter. They bought and wore matching gold bands on their left ring finger but maintained separate residences. When congregants invited Wood out socially, Hugh usually went along. Some grasped the nature of their relationship, others did not.

Was Wood "out" or not? In an interview I conducted with him last week he says he "came out" in 1957 when he published a short article called "Spiritual Exercises" in a gay men's physique magazine. He used his real name and it was printed with a clear head shot, the same one he later used for his book. In an earlier interview with Stephen Law, Wood described an unambiguous public declaration of his sexuality more typical of what Americans consider "coming out." When Hugh died in 1986 a sympathetic parishioner said, "I am so sorry your friend has died."

"He wasn't my friend,"Wood declared, "he was my partner." It was the first time he confronted the ambiguity that had allowed him and Hugh to lead the life they did while still actively and openly advocating for gay rights.

Being "out" enabled people to publicly fight against oppression while simultaneously providing a visible role model for lesbians and gays who believed they were abnormal, deviant, and sinners. For that reason, being out had a measurable historical impact. Wood's book is case in point. He received hundreds of letters from lesbians and gays who expressed relief at having a positive view of themselves put forward, but who were still too afraid to sign their own names at the bottom of the page.

Did Wood come out in 1957 or 1986? Or is "outness" too blunt an instrument for understanding the history of queer resistance politics? Perhaps Wood's story suggests that we need a different metric for measuring "outness" in the 50s and 60s than we do for the 70s and after. What do you think?

(Special thanks to Alan Miller of the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives for putting me on to Wood's work)

crossposted to

Like the Elise Chenier Facebook Page | Like the From Outlaws to In-Laws Facebook Page